Performances for the gods: Japanese Noh Theater

Japanese Noh theatre is one of the oldest dramatic forms in world. The early developments of Noh lie in the festive entertainment of various kinds (dance, simple plays) performed at temples and shrines in the 12th and 13th centuries. Noh drama for much of its history was favored by the samurai, priest and aristocratic classes. Unlike Western theatre, the Noh performer is more a storyteller who suggests the meaning of the play with his movements and through his appearance or costume. Until 100 years ago, the audience was intimately familiar with the plot and the historical or mythological background of the play and knew how to interpret and appreciate symbolic and indirect references to Japanese history, much like early audiences at Shakespeare’s plays. Today, most Japanese require "notes" to understand what they are seeing in a Noh play.

Nearly all of the Noh plays performed today were written by the start of the 17th century. The vast majority of the core Noh repertoire were written by Kan’ami Kiyotsugu (1333-84) and his son, Zeami Motokiyo (136-1443) in Kyoto. Zeami, as the father of Noh, developed most of the principles upon which Noh theatre has always been based. Today, of the roughly 2,000 Noh texts that are known to exist, only 230 core works are still performed regularly. The Noh world has two centers: Kyoto and Tokyo.

Dramatically, the Noh theatre is by no means as complicated as Western theatre forms. Essentially, there is no plot and everything on stage takes place very slowly. The plays are quite short: not much more than an hour, during which only two or three hundred lines will be chanted. The plays are usually tragic and related to themes beyond the human realm in a world full of gods, demons and ghosts. The setting is generally a very simple place that has some special significance to the main character or actor (shite). The other main performers on the stage are the waki (playing the role of a Buddhist priest or the opposite role of the shite) and the one or two actors that “assist” the shite and waki. All the performers in a Noh play are men, even when the role is female.

In addition to the main actors on the stage, who often wear haunting, symbolic wooden Noh masks and carry one of two simple props--a fan or a wooden staff--Noh performances involve a chorus of 8 singers and up to four musicians playing one of two kinds of instruments (3 sizes of drums and a flute). The drum rhythm is used to indicate the degree of tension the main actor is trying to convey to the audience. All the elements blend into a single harmonic whole and not one single element dominates.

In ancient times, when a theatre event could last most of the day, comic relief kyogen plays were often performed between each Noh play. Today, kyogen exists as a theatre form that is usually separate from Noh, though exceptions like the annual Takagi Noh (Fire-light Noh) in June have continued.

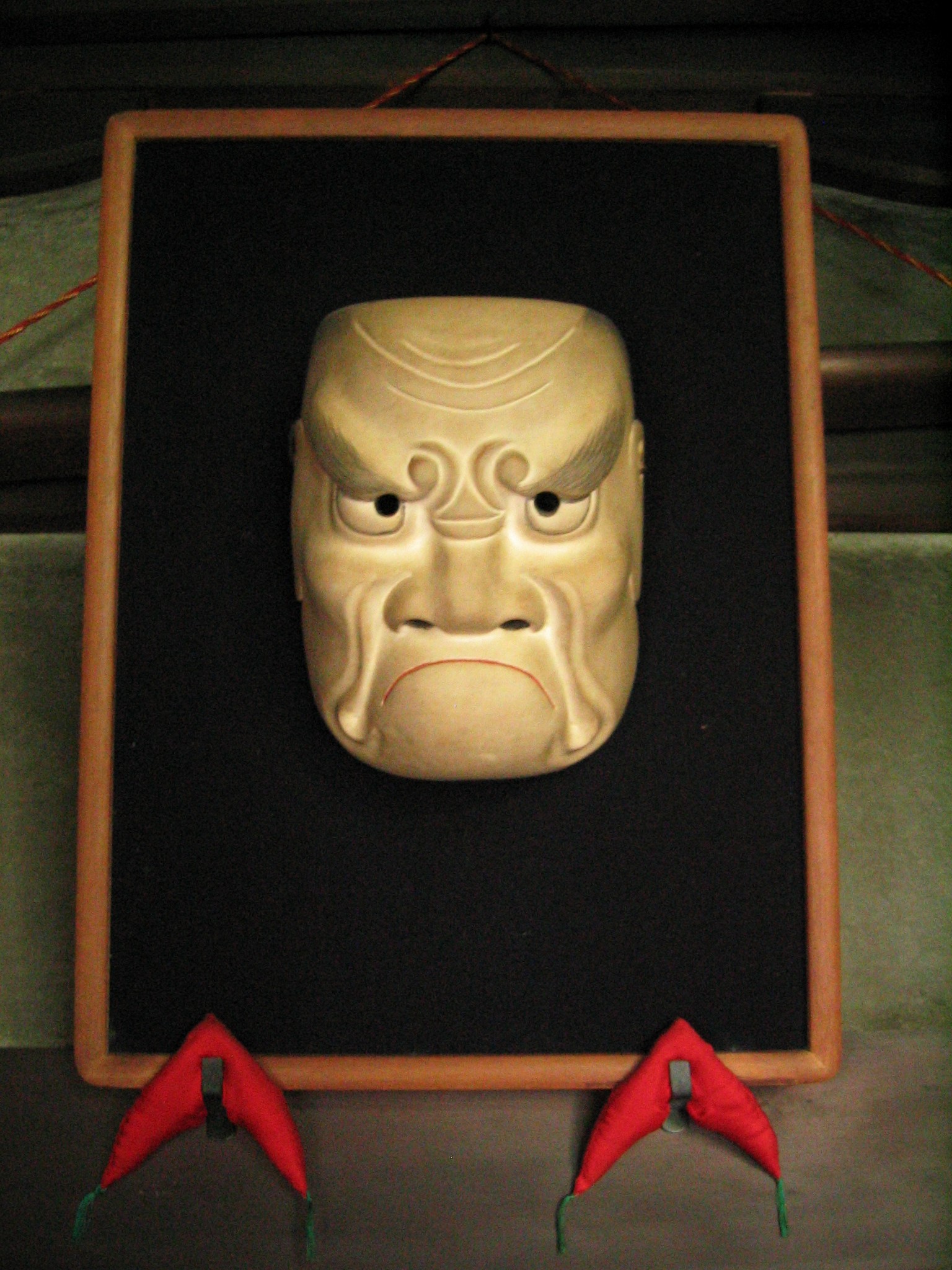

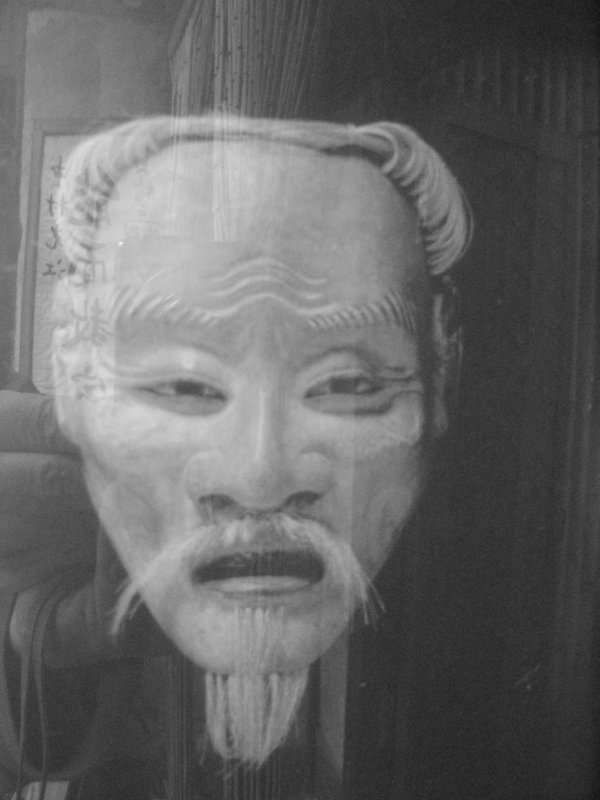

The moving spectacle of the Noh is inseparable from the striking, often haunting beauty of Noh masks, which can be divided into five basic categories: shin (gods), nan (men), jo (women), kyou (crazy entities), and ki (demons). There are about 80 distinct masks. It takes a master mask maker about one month to finish a single mask.

Though many Noh masks appear to be expressionless, they actually function to express emotions ranging from joy and anger to sorrow or pleasure. Worn with a downward tilt, the mask is said to express sorrow. Tilted upward, the mask conversely is interpreted to express joy and laughter. A Noh mask contains the very soul of the character it depicts. When an actor begins to prepare for a role, it is to the mask that he or she looks to discover the essence of the character. Until the mask is in place, the actor is simply himself, but once it is on, he is transformed—body and soul—into that character. Given the central importance of the mask to Noh, it is no surprise that every Noh school treats its masks with a profound reverence. The leading schools often use masks in their performances that are hundreds of years old!

Kyoto has two major Noh performance groups: the Kawamura family and the Kongo family. In Tokyo, the biggest Noh schools the Tokyo Kanze Noh Theater, and Hosho Noh Theater. Plays are held regularly and are not expensive. Try and experience the wonders of this dramatic form at least once: you won’t be disappointed.

Content by Ian Martin Ropke, owner of Your Japan Private Tours (est. 1990). I have been planning, designing, and making custom Japan private tours on all five Japanese islands since the early 1990s. I work closely with Japan private tour clients and have worked for all kinds of families, companies, and individuals since 1990. Clients find me mostly via organic search, and I advertise my custom Japan private tours & travel services on www.japan-guide.com, which has the best all-Japan English content & maps in Japan! If you are going to Japan and you understand the advantages of private travel, consider my services for your next trip. And thank you for reading my content. I, Ian Martin Ropke (unique on Google Search), am also a serious nonfiction and fiction writer, a startup founder (NexussPlus.com), and a spiritual wood sculptor. Learn more!

Noh Masks: Faces of life & death

The moving spectacle of the Noh theatre is inseparable from the striking, often haunting beauty of Noh-men, or masks. The art of making Noh masks was perfected in the Muromachi period (1333-1568) when the drama form was first developed. Altogether there are approximately 80 different Noh masks separated into five basic categories. Much more than a work of art, Noh masks contains the very soul of the character they represent.

When an actor begins to prepare for a role, it is to the mask that he or she looks to discover the essence of the character. Until the mask is in place, the actor is simply himself, but once it is on, he is transformed—body and soul—into that character. Given the central importance of the mask to Noh, it is no surprise that every Noh school treats its masks with a profound reverence.

Japanese cypress (hinoki) is used for making the masks. After roughly carving out the mask shape (front and back), the location of the nose, eyes and mouth are approximated. Then, with increasingly finer chisels the final shape of the mask and its individual parts are perfected. The outer surface of the mask is covered with 15-20 coats of powdered shell mixed with deer-bone glue. Each separate coat is polished down before the next coat is applied. Hair (from the tail of a horse) is applied to some masks at the very end. Then, though not always, the outer finish is deliberately chipped to give the mask an old feeling. Altogether, it takes a master about one month to finish a single mask.

Excellent Noh masks can be seen at Kyoto's Fureaikan Museum (Kyoto Museum of Traditional crafts). And The Tokyo National Museum has more than 200 Noh masks in its collection and many are on permanent display.

The Mysterious World of Noh Masks: Interview with Ms. Mitsue Nakamura

Noh is one of the oldest theatre entertainment forms in the world. The very beginnings are unknown, but it was acted out before and enjoyed by people at least 600 years ago in the Muromachi period (1336-1573) and little has changed since then. Even the language used in Noh plays is ancient. Noh performances involve actors and musicians on stage and yet for many the most important energies are mirrored in the special masks that have been carefully created from blocks of wood for the actors.

All Noh performers, except the musicians, wear masks. This means that the character’s facial feelings are expressed by the mask in combination with the voice and movement of the actor on the stage. This interview is with Ms. Mitsue Nakamura, a Noh mask maker. [The interview is from 2007 but in the virtually unchanging world of Noh theater . . . all things remain the same . . .]

Ms. Nakamura came to Kyoto to study Western oil painting at one of Kyoto’s leading art universities. She was hardly involved with the traditional world of Japanese art and culture until she was 36 years old. "But one day I came across a book about Noh masks and my life changed immediately," she recalls. She was completely drawn into the mysterious world of Noh masks from one day to the next. At that time, she was a housewife. Soon she was taking lessons and learning the intricate steps required to create these delicate masks from blocks of fine cypress wood.

"I always loved painting on flat surfaces, but I was especially interested in drawing people’s faces, especially painting facial expressions with oils. Therefore, it was only natural that I was so attracted to Noh masks because they were a mirror for my earliest and deepest interests."

Many other students in her class took the Noh mask making class just for fun. However, she was determined to become a professional Noh mask maker early on. This made a huge difference in her progress and in the guidance she received from her teachers. She studied really hard from the very beginning. Later she was lucky enough to have the opportunity to study under one of the best Noh mask makers in Japan. He was a true master of the mask world and that played a big role in Ms. Nakamura’s eventual success as a professional Noh mask maker.

Respect for tradition: learning from the past

The world of the Noh performer is very mysterious and private and based on a hereditary system. Noh mask making was also the exclusive domain of a single family until the Meiji period (1868-1912). However, that family eventually died out and the field became open to individuals and a certain amount of rivalry and competition. "To be successful in this world requires an exceptional effort and an incredible amount of time."

What is difficult about being a Noh mask maker is that one has to learn how to make several hundreds kinds of Noh masks. There are many types of masks, for example, young women, old women, jealous women, hannya demon women, etc. Some masks are used only in one specific Noh play and that makes them especially rare and powerful. These kinds of masks are hardly ever handled by human hands, and this also gives them special power. "I was lucky in this respect because of my teacher’s very high ranking in the Noh mask world. He had almost every kind of Noh mask, so that I was able to learn from them as much as I wanted. To learn from the ‘real’ is very important."

When you see a Noh mask, you feel that it is old, very old. However, this look has been created intentionally. Antiquity and formality are highly respected in the Noh world, so new masks require special techniques to give them a timeless feeling.

"I feel that human creativity is very much based on a respect for tradition and for those that came before us and showed us the way, especially with something as old and essentially unchanging as the Noh world. For me, a deep respect for tradition and the works left by those who have come before me was and is the only way I can make something that has meaning."

Masks are living, changing faces

Noh masks are created through a series of stages: first a block of hinoki cypress wood is marked up with a pencil with the basic shape of a face, an oval; then details emerge from the oval shape in terms of proportion and expression; finally, the mask is painted with one of several special paints that add to the expression and suggest that the mask is old.

In Japanese, a person’s face that is cold and without emotion is referred to as "‘"a face like a Noh mask." This is true in a way because Noh masks can’t change their essential shape or expression. However, to our surprise, masks change and appear differently as the emotion expressed by the Noh actor changes. The effect is subtle, but we do sense that the mask is alive when it is on the Noh stage. It has an inner range of emotions that can rise to the surface. Anger, sadness, pleasure, melancholy, hate, jealousy, shyness, excitement, and many other delicate feelings can be felt from the masks. The higher the subtlety in the work of the mask maker the easier it becomes for a mask to express different feelings.

"I am 60 years old now. Twenty-five years have passed since I encountered my first Noh mask. In the coming years, I will do my best work. I have made many compromises and sacrifices to follow the way of the Noh mask maker, but this is the world I have dedicated my soul to."

Return to the Japanese culture essay index.

Content by Ian Martin Ropke, owner of Your Japan Private Tours (est. 1990). I have been planning, designing, and making custom Japan private tours on all five Japanese islands since the early 1990s. I work closely with Japan private tour clients and have worked for all kinds of families, companies, and individuals since 1990. Clients find me mostly via organic search, and I advertise my custom Japan private tours & travel services on www.japan-guide.com, which has the best all-Japan English content & maps in Japan! If you are going to Japan and you understand the advantages of private travel, consider my services for your next trip. And thank you for reading my content. I, Ian Martin Ropke (unique on Google Search), am also a serious nonfiction and fiction writer, a startup founder (NexussPlus.com), and a spiritual wood sculptor. Learn more!