Japan November travel overview: season, food, nature, events

November is widely considered to be the “awesome” autumn month for Japan travel. And it's extremely important to understand that Japanese domestic tourists are by far the most dominant group in the Japan November travel season. Specifically, Kyoto welcomes about 10 million Japanese tourists in November making it very challenging to find hotel rooms and serenity in the Old Capital. So, if you are planning to visit Japan in November you really do have to make plans well in advance unless you have an “unlimited” budget. [Just so you know: we have all kinds of tricks to avoid crowds and find serenity in Kyoto in super peak season.]

However, despite the Japanese maple leaf hunting hordes, November is stunningly beautiful and some of the year’s biggest events and exhibitions take place in this month.

November isn’t just about Kyoto, Nara and the “trending” weekend getaways near Tokyo. Many international travelers spend their November travel itineraries on the island of Kyushu or exploring the late-autumn-early-winter moods of Hokkaido way up north. The northern side of the Japanese Alps, from Toyama all the way up to Niigata, are also popular November destinations for autumn colors and seaside wonders.

In November, afternoon temperatures range from roughly 14ºC to 18ºC (57°F to 64°F) while morning and evening temperatures are in the 7ºC to 12ºC range (45°F to 54°F). With few exceptions, November is typhoon free, and rain is minimal.

In the Japanese tea ceremony, the month of November has been poetically captured with “goma” associations that capture the essence of each 10-day period: early November, mid-November, late November. These key words and themes that have been classically repeated in Japan for more than 1,200 years. The November goma key words can help you “imagine” what to expect when you travel in Japan in that month. Early November themes: Inoko baby boar; Ichiyo: a single leaf on a tree. Mid-November themes: Shusho autumn frost; Kuchiki decaying trees or wood. Late November themes: Iso Chidori beach plovers (shore birds); Hatsu Go-ri first freezing, first ice.

In traditional homes and in the tea ceremony, November is the month when the winter sunken hearth is fired up after nearly 6 months of unuse. In November, charcoal is laid in the hearth below the floor level and the tea that was picked in May and sealed in earthenware jars is ground to powder and prepared for drinking for the first time.

As the temperatures cool, traditional sweets go from room temperature to warm and toasty. A national favorite would be zenzai, Japan’s traditional sweet bean soup served with mochi rice cakes or chestnuts

Other November themes to be on the lookout for in the art and culture centers you might visit include charcoal, pine needles, winter wind, sudden but brief rain, and frosty nights.

- Japan November travel food highlights

- Japan November travel tree and flower highlights

- Japan November travel festival highlights

- Wagashi Japanese tea sweets: edible works of art

- Hokusai: Japan’s most innovative woodblock artist

- Interview with master kimono artist Katsuhiko Hayashi

Content by Ian Martin Ropke, owner of Your Japan Private Tours (est. 1990). I have been planning, designing, and making custom Japan private tours on all five Japanese islands since the early 1990s. I work closely with Japan private tour clients and have worked for all kinds of families, companies, and individuals since 1990. Clients find me mostly via organic search, and I advertise my custom Japan private tours & travel services on www.japan-guide.com, which has the best all-Japan English content & maps in Japan! If you are going to Japan and you understand the advantages of private travel, consider my services for your next trip. And thank you for reading my content. I, Ian Martin Ropke (unique on Google Search), am also a serious nonfiction and fiction writer, a startup founder (NexussPlus.com), and a spiritual wood sculptor. Learn more!

Japan November travel food highlights

November is a huge month for restaurants all over Japan because so many Japanese tourists are out and about spending money on great eateries. And because of all the autumn months (Sept, Oct, Nov) November is the most celebrated in traditional culture forms (paintings, ceramics, etc.) so there is a lot of social activity in town and in the countryside. The month of November is huge for seafood lovers (see below) and then the high notes are fresh apples (big ones!) and the finest spinach dishes of the year.

I would highly recommend eating a lot of Japanese apples this month, for snacks during the day mostly. Just visit a good supermarket or, even better, the basement deli floor of all big department stores and get the best apples you can find. Zero of them will be from outside of Japan. All of them will be Japanese and some elderly Americans have a flashback when eating a Japanese apple.

Kaki persimmons: Kaki are an orange Japanese fruit that come into season in November. They are extremely bitter before they ripen. When ripe, they are sweet with a unique citrus-like taste. Kaki and kaki flavored desserts are widely available in Japan in late autumn.

The seafood world of Japan has its finest season in autumn and winter (generally November to March). This is a time to pay special attention the offerings of the week at top seafood specialty restaurants, and in good quality izakaya and robatayaki settings. Look closely at the menu (if in English) or learn what you can from your chefs or serving personnel about the seafood treats you can choose in November (right through to March)! Here are just a few top options:

Kinosaki crab: Also known as Matsuba (pine needle) crab these tasty male snow crabs come into season in November (till March) in the Sea of Japan off the Kinosaki coast primarily. The tender, fluffy Kinosaki crab meat is featured on many menus throughout the country as are “kani miso” (crab innards).

Buri yellowtail: Better known as hamachi or buri in Japanese, yellowtail can be eaten cooked or raw (as sashimi!), and from November to March the fat content of this fish species is at its highest. Some of the fish consumed are wild, but a considerable amount is farmed.

Chidai crimson sea bream: There are nearly 300 kinds of sea bream or tai in Japanese waters. Sea bream types that are highly popular at sashimi counters across Japan include red sea bream (madai), crimson sea bream (chidai) and yellowback sea bream (kidai). Tai in Japan is known as the king of white fish meat.

Ginzake Coho salmon: Salmon is available year round in Japan but the November to March season is the best because the salmon meat is so fatty. The expensive wild Coho salmon are available, but you have to ask for it! The rest are fish farmed mainly by the Marukin corporation (since 1977!). So, if your budget is tight ask specifically for farmed Coho salmon (yōshoku ginzake).

Katsuo bonito or skipjack tuna: In the world of sushi and sashimi, maguro or tuna reigns supreme and the better the quality the higher the price! But the tuna variety that is still the most widely eaten is katsuo or skipjack tuna. Katsuo fish flakes are used for miso soup broth in restaurants and households. Skipjack tuna, which is fat rich from Nov. to March, can be prepared in many ways. The most popular preparation is called tataki sashimi, which is bonito seared on the outside but still raw on the inside. Katsuo, believe it or not, is what the gods are fed in the top Shinto shrines across the country! I have seen the priests of Kasuga Grand Shrine in Nara with cedar serving trays laden with beautiful whole skipjack tuna at sunset (dinner for the gods).

Sanma Pacific saury: Pacific saury or sanma is mostly fished in the waters off the Kii Peninsula and the Wakayama Peninsula and November to March is the finest catch of the year. Sanma is generally served salted and grilled (or broiled) whole, with a garnish of oroshi grated daikon, together with a bowl of rice and a serving of miso soup. Sanma intestines are bitter, but most Japanese appreciate this and eat the entire fish.

Shishamo Japanese longfin smelt: Shishamo is a kind of smelt that is primarily caught in Hokkaido waters. This “thin” fish is about 15 centimeters (6 in) in length and is nearly always grilled or fried whole and served with its roe intact. And Nov. to March is peak season for this fish type. Wild catches have declined in recent years, and commercial sea farming is in progress.

- Japan November travel food highlights

- Japan November travel tree and flower highlights

- Japan November travel festival highlights

- Wagashi Japanese tea sweets: edible works of art

- Hokusai: Japan’s most innovative woodblock artist

- Interview with master kimono artist Katsuhiko Hayashi

Japan November travel tree and flower highlights

Chrysanthemums: Few tourists understand that the kiku chrysanthemum is symbolic of Japan’s imperial family. They stay in bloom for a long time and the imperial family has been in “bloom” for a long time. Chrysanthemums are frequently mentioned and depicted in Japanese literature and art. They even decorate one side of Japanese 50-yen coins. Growing ornamental kiku flowers is very popular in Japan, even today. And chrysanthemum festivals and competitions are held throughout Japan in October and November as well as in the exceptional displays at big temples and shrines. Note: Do not give kiku flowers as gift as they are strongly associated with death and Buddhist funerals.

Outstanding November maple viewing locations you might not know: Icho Namiki Ginko Avenue (Tokyo): The fall golden ginkgo (icho) is Tokyo’s official tree (but you can see them in many places across the country). But in Tokyo in November do stroll along Icho Namiki or "Ginkgo Avenue" in the Meiji-jingu Gaien Park for golden leaves and upscale coffee shops (outdoor and in). Koishikawa Korakuen Gardens (Tokyo): Like Rikugien (see below), Koishikawa Korakuen is considered to be one of Tokyo's finest landscape gardens and for autumn colors it yields a compact picture of colored perfection. Koyasan (southeast of Osaka): This “wildly” popular spiritual mecca has an incredible range of attractions, and the November colors are one of them. The views of the mountains all around are also colored in noticeable ways. Kurobe Gorge (northern Japan Alps): The northern Japan Alps entry point of Kurobe Gorge is an outstanding natural destination in all seasons but in autumn the colors are truly awesome! Kurobe Gorge is about 2.5 hours by train from Tokyo, so can be a long day trip. Mount Takao (Tokyo): Takaosan or Mount Takao is fairly large and undeveloped park area that is very close to Tokyo (50 min. from Shinjuku) and in November autumn colors are part of the attraction. Naruko Gorge (northwest of Tokyo): This steep gorge is about 4 hours north of Tokyo, inland from Sendai. Naruko Gorge is one of the Tohoku region's top autumn color spots (i.e., maybe avoid on weekends!). Rikugien Gardens (Tokyo): Rikugien is one of Tokyo's top historical Japanese landscape gardens and very bright in autumn. During peak momiji maple season the garden is illuminated. Shosenkyo Gorge (Kofu, just west of Tokyo): Considered to be Japan's most beautiful gorge, the Shosenkyo Gorge, just west of Tokyo, is stunning to a high degree during the autumn season. Yoshiminedera Temple (Kyoto): Like Kiyomizudera Temple’s views from the eastern ridge of Kyoto, Yoshiminedera overviews the city from the western hills. It is a known autumn leaf viewing spot, but you won’t see many foreign tourists there (again, avoid on weekends).

Japan November travel festival highlights

Shichi-go-san (most of Nov.; all over Japan): Traditionally on 11/15, but nowadays throughout the month of November (especially the Sundays on either side of the 15th), seven, five, and three year old boys and girls, outrageously dressed up in bright kimono or formal suits, visit (with their parents) their local shrine, or, even better, one of the biggest ones in town, to celebrate 7-5-3 and pray for their health and good fortune. Don’t miss this event!!! The best places in Kyoto are: Heian Shrine, Kamigamo Shrine, and Yasaka Shrine. Special Temple Openings (all Nov.; Kyoto): The spectacular colors of autumn blending with Kyoto’s ancient and weathered wooden buildings turn nearly every scene into a living work of art. But autumn in Kyoto holds even greater delights, because only at this time of year do numerous temple open to the public their stunning collections of Buddhist art, accumulated over centuries. Don't miss this special chance to see what lies hidden away behind the walls of Kyoto's great temple complexes. Design Festa (early November; Tokyo): Nearly 10,000 booths by mostly Tokyo-based artists, designers, craft artists, performance artists and musicians. The Annual Gion Odori Dances (11/1-10; Kyoto): Among the gorgeous sights that lure visitors to Kyoto every autumn are traditional performances featuring geisha and young maiko — apprentice geisha — dressed in richly decorated kimono. The exquisite Gion Odori dances have long been celebrated in every medium of Japanese art, from poetry to painting, from kabuki to film. At the Gion Kaikan Theater, southeast of Gion Corner; at 13:00 and 15:30. Tickets ¥3,300 (¥3,800 with tea service). Karatsu Kunchi Festival (Nov. 2-4; Karatsu): A small town festival with a parade of old floats that date to the 1800s that weigh up to 3 tons. The highlight of the festival is the challenge of dragging the floats across the town beach. Kyushu Sumo tournament (mid-Nov. to late Nov.; Fukuoka): The last of the six annual tournaments of professional Sumo each year. The fans in Fukuoka tend to be enthusiastic because Sumo only comes to town each November.

- Japan November travel food highlights

- Japan November travel tree and flower highlights

- Japan November travel festival highlights

- Wagashi Japanese tea sweets: edible works of art

- Hokusai: Japan’s most innovative woodblock artist

- Interview with master kimono artist Katsuhiko Hayashi

Wagashi Japanese tea sweets: edible works of art

The history of wagashi, fine Japanese sweets, is inseparable from the history of white sugar, which first appeared in Japan in 1603 as a valued import from the West. For Japan, a country with a long-established sweets tradition but which had only ever known brown sugar, white sugar was a revolutionary product . It became so much in demand that from the 18 century onwards domestic refined sugar production was established with the strong support of the 8th Tokugawa shogun. From the beginning, trade in products using white sugar became the official monopoly of shops designated with the special term jogashi. Jogashi confectioneries are classified into three broad groups: Cha-gashi (tea ceremony sweets), Kusenga (sweets temple and shrine offerings), and Kenjoga (sweets specially reserved for the Imperial family).

The status of jogashi shops was so high that they had total creative control over their products, as well as the established right to never have to enter a house through the back door when receiving or delivering an order. At the height of the Edo period, there were over 240 Jogashi shops in Kyoto. Today, only 40 or so with a history of more than 100 years, remain. Despite the strong influence of Western sweets, wagashi continue to preserve the sophisticated image and quality for which the Japanese tea ceremony is legendary.

Best wagashi shop and experiences in Tokyo:

Toraya, Akasaka: Toraya is a celebrated player in the world of high quality world of wagashi, with 500 years of orders from the imperial court. Their main shop is in upscale Akasaka, but they also have excellent branches in the Ginza, Marunouchi (Tokyo Station area), Roppongi and Nihonbashi. Their signature treat is yokan, a bar of jellied red bean paste. And Toraya’s aesthetic interpretations of wagashi are well worth experiencing.

Aono, Akasaka: Aono got started in the wagashi world in 1899 and now has five branches across Tokyo. Their Akasaka mochi, wrapped in a beautiful furoshiki cloth, is made with brown sugar and walnuts. They also stock a seasonally changing range of namagashi that use fruit jellies or sweetened bean paste and are carefully “designed” with seasonal and natural motifs including real leaves and flowers.

Tsuruya Yoshinobu, Nihonbashi-Ginza: This famous Kyoto wagashi shop opened its Tokyo branch in 2014 in the Nihonbashi-Ginza area (in the Coredo complex), not far from the famous Mitsukoshi department store. The shop has a retail counter zone and a tearoom, and many wagashi display cases. At the counter you can order handmade namawagashi that are freshly prepared before your eyes. Website: http://tokyo-mise.jp/

Aoya no Tonari, Aobadai: Aoya no Tonari (a café setting) serves freshly-made “Kyoto-style” wagashi and sweets. This is an intimate experience as the shop is in an old, renovated house in Aobadai (about 1.5 km southwest of Shibuya Station). Everything they make is free of preservatives, additives, and white sugar. The Kyoto-born owner-chef is well known for his petite gokoku namafu-dango, or wheat gluten dumplings. Picnic takeaway boxes? No problem! Closed Mondays. Website: http://www.aoya-nakameguro.com

Best wagashi shop and experiences in Kyoto:

Kanshun-do, Kyoto National Museum area: Though Kanshun-do was formally established as a company in 1865, the Fujiya family has been renowned in the wagashi world since the late 16th century. Many of the shop's recipes are closely guarded secrets, and some are so old in origin that few other shops can make them. Since the beginning, Kanshun-do has maintained strong connections with temples and shrines in Kyoto, providing them with a selection of seasonally created sweets. Today, with the ever growing popularity of the Japanese tea ceremony abroad, Kanshun-do is actively developing new styles of wagashi for the international market. Their internationally oriented products maintain the old-time traditions of wagashi while taking into account the particular preferences of foreigners. Kanshun-do's creations combine seasonal nuances with color, shape, and exquisite taste. Because at Kanshun-do, wagashi is considered to be an art.

Oimatsu, Kitano | Arashiyama: Oimatsu's historical background in Kyoto, particularly in the Arashiyama area, where Kukai, the great founder and saint of Shingo Buddhism first introduced Chinese sweets to Japan, is legendary. The Oimatsu Arashiyama shop has preserved a quiet atmosphere of historical ambience in its subtle, sophisticated style, and serves a variety of sweets with the finest varieties of Japanese tea in its tea salon. Oimatsu's Kitano shop, established in the Muromachi Period next to Kitano Shrine, an area that was once one of Kyoto's leading geisha entertainment districts, features an open-air tea salon in the grounds of Kitano Shrine which is open throughout the year. Recommended treats are their walnut or kumquat lightly sugar-coated cookies.

Kagizen Yoshifusa, Gion: Kagizen Yoshifusa is over 300 years old and it’s my absolutely most favorite wagashi shop in all of Japan: so much to look at and the back tea room is serene while Gion rages out front. They have two shops: one on Shijo Street in the Gion area, and the other near Kodai-ji Temple. Kagizen Yoshifusa is especially famous for its kuzukiri (arrowroot noodles served with sweet sauce) but the seasonal wagashi glass case in the main shop is really the main attraction, in my opinion: such delicate art works that you can take away or savor in the back tearoom. Exquisite! The main shop is simple enough but if you look around you can see the history of their craft on the walls (up high) and some really outstanding wooden chests designed in the early 20th century by master woodworker Kuroda. Closed on Mon. (main shop) and Wed. (Kodaiji shop).

Toraya Ichijoji, west of the Old Imperial Palace: The building alone tells you that Toraya Ichijoji is a serious place for aesthetics and wagashi culture. Located near the Kyoto Imperial Palace, Toraya Ichijo shop is where Toraya began providing sweets to the Imperial court in 1628. When the imperial court moved to Tokyo in 1868, Toraya set up shop there quickly and has stayed in Tokyo as well (see above). At Toraya Ichijoji, visitors can enjoy Toraya’s exquisite confections while viewing a beautiful landscape garden featuring an Inari Shrine and an Edo-period kura storehouse. Website: https://global.toraya-group.co.jp/pages/kyoto-ichijo-store

Saryo Housen, north side of the Shimogamo Shrine area; hard to find!: Saryou Housen Japanese garden café is a hidden treasure spot for tea, wagashi and the stunning garden views. They are famous for their sweet and chewy warabi-mochi and their handcrafted top-level jo-namagashi. Closed Wednesdays & Thursdays. Website: http://www.housendo.com/housen.html.

- Japan November travel food highlights

- Japan November travel tree and flower highlights

- Japan November travel festival highlights

- Wagashi Japanese tea sweets: edible works of art

- Hokusai: Japan’s most innovative woodblock artist

- Interview with master kimono artist Katsuhiko Hayashi

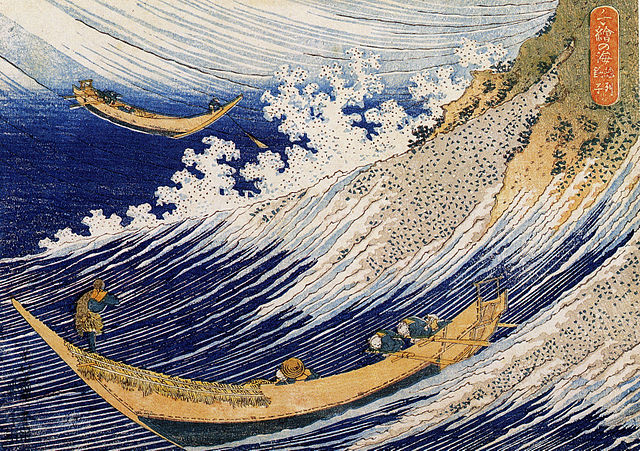

Hokusai: Japan’s most innovative woodblock artist

Katsushika Hokusai (1760 - 1849) — the ukiyoe master whose style, with its dynamic composition and innovative coloring, strongly influenced the French Impressionists is perhaps Japan’s most famous artist. He was born in Edo (present-day Tokyo) and started working as an apprentice at a rental bookstore when he was only 6 years old. Recognizing his passion for art, after briefly studying with a master wood sculptor, he entered the school of Katsukawa Shunsho, an ukiyoe painter, at the age of 19.

When Hokusai was 34, he was expelled from the school, because he had studied the art of another school — the famous and classical nihonga Kano School — without the permission of his own master. This, however, was very much to Hokusai’s advantage. Now he could freely study the art of nihonga and expand his artistic horizons to encompass Chinese and Western painting traditions as well. Nothing could have suited him more. Hokusai was not the kind of artist who could be satisfied with just one subject or method. Diversity and experimentation were key to his artistic development. He was constantly trying new genres, which ultimately contributed to the extreme sophistication of his artistic talents. The fact that he changed his artistic name as many as 30 times clearly indicates that he was continually developed as an artist.

His artistic sensibility and skills remained sharp until very late in his life. The famous nishiki-e work shown here — Fugaku Sanju Rokkei — was unveiled to the public when Hokusai was already 60 years of age.

One episode, in particular, shows the free spirit for which Hokusai was well known. One day the shogun Tokugawa Ienari asked Hokusai to paint in his presence. First, Hokusai drew the classical ka-cho-fu-getsu, or "The Natural beauty of flowers, birds, under a bright Moon, in a cool breeze," and showed it to the shogun. After that, he took out a long piece of Chinese paper from his kimono, placed it on the floor and drew a dark blue, thick line straight down the length of the paper. Then he took a chicken he had brought with him, dipped its feet in red ink, and released it on the paper! Showing the "work" with the chicken's foot prints all over it, Hokusai proudly told the shogun, "This is the Tatsuta River," referring to a poem about the beauty of Nara’s Tatsuta River in autumn covered with bright, red maple leaves from One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets, a classic anthology of Japanese poetry.

Hokusai was a man who loved freedom and change. He lived in 93 different residences over his lifetime. Changing his life style continuously was probably how he kept his dynamic and innovative artistic sense alive and fresh. As they say, "a rolling stone gathers no moss." Hokusai would certainly have agreed.

- Japan November travel food highlights

- Japan November travel tree and flower highlights

- Japan November travel festival highlights

- Wagashi Japanese tea sweets: edible works of art

- Hokusai: Japan’s most innovative woodblock artist

- Interview with master kimono artist Katsuhiko Hayashi

Interview with master kimono artist Katsuhiko Hayashi

Katsuhiko Hayashi (born in Kyoto in 1937) has spent his adult life doing what he loves: sketching flowers and plants and then using his sketches and feelings to create original, unforgettable patterns for handmade kimono. He transfers designs to silk using the rokketsu dyeing process which uses very thin wax line barriers to control the dye from staining other areas of the pattern. In 1974, he founded his own design and production studio in Muko City, a little southwest of Kyoto.

He has had one-man shows in New York (1984) and Vancouver (1992), won many prestigious prizes for his work in Japan (and one in Italy). As an artist he feels that his kimonos are works of art and not just a fine article of clothing. His work ranges from classic, traditional patterns to bold modern motifs. The main themes of his work have always been the natural wonder, grace and beauty of flowers and water. Mr. Hayashi speaks English and welcomes visitors interested in his work or kimono to his studio (Tel/Fax: 075-933-3114).

YJPT: How has the kimono industry changed since the Japanese economic bubble collapsed?

KH: In the area that I specialize in, there has been a lot less change than you might think. I work in the most expensive area of kimono design. The people who buy the things I design are not really concerned with money.

I sell my creations to a kimono wholesaler, who then sells them to the retail shops that have wealthy people for clients. On occasion, I sell directly to a customer. In the old days, I created things that the wholesalers requested. However, I now have a name and so things are reversed. Now I make what I want and convince the wholesaler to accept it.

Naturally, my dream is to make things for private customers only. But the kimono business is a very conservative one and clients like their privacy too. Nevertheless, I find it outrageous that a wholesaler, or retail shop can mark one of my creations up by 1000%. These people are not interested in the beauty and culture that kimono symbolize. They are motivated exclusively by money. If you are interested in getting good value, go directly to the artist.

YJPT: What are your feelings about the young people of Japan today compared to the young people of your generation? How are they different?

KH: In my youth, I felt that young people had solid dreams and realistic goals in regard to what they wanted to do or the kind of person they wanted to become. Today, I feel that young people do not have any strong motivation or dreams regarding the life that lies before them. One of the reasons for this may be that they are disappointed in or were not inspired by their parents. I feel that parents since my parents were not equipped with the right stuff to inspire people, least of all their children. They were brought up in a complacent, economy-driven social system designed to create obedient workers. The dramatic slowdown in the Japanese economy over the past decade has only made things worse.

I understand that young people want to rebel against the system. The education system is still trying to train them for a society and economy that differs considerably from the real world around them. Young people can feel that the system does not represent their values, but at the same time they do not where to find new values. I think the education system should be redesigned to emphasize creativity and beauty. In this way, they would be able to appreciate nature more, grow their sense of beauty and possibly find a deeper and more meaningful spirituality. All three of these things were part of nearly all Japanese people until the end of the war.

YJPT: What is your favorite season and why?

KH: I love autumn and that special feeling of solitude that comes at twilight.

Japan month by month private travel & culture summary index

Japan spring travel: Mar, April, May. Learn more!

Japan summer travel: June, July, August. Learn more!

Japan autumn travel: Sept, Oct, Nov. Learn more!

Japan winter travel: Dec, Jan, Feb. Learn more!

Content by Ian Martin Ropke, owner of Your Japan Private Tours (est. 1990). I have been planning, designing, and making custom Japan private tours on all five Japanese islands since the early 1990s. I work closely with Japan private tour clients and have worked for all kinds of families, companies, and individuals since 1990. Clients find me mostly via organic search, and I advertise my custom Japan private tours & travel services on www.japan-guide.com, which has the best all-Japan English content & maps in Japan! If you are going to Japan and you understand the advantages of private travel, consider my services for your next trip. And thank you for reading my content. I, Ian Martin Ropke (unique on Google Search), am also a serious nonfiction and fiction writer, a startup founder (NexussPlus.com), and a spiritual wood sculptor. Learn more!