Japan October travel overview: season, food, nature, events

The month of October is the best autumn month to travel in Japan. October is great for fall colors, if you know where to go, and until about the 20th the huge momiji maple leaf crowds of Kyoto (in particular) are out of sight. And just so you know, the exceptionally beautiful fall colors of Japan also begin much earlier at higher elevations in the Japanese Alps and further up north (Hokkaido, Aomori, Akita). So, October is an excellent month (particularly the first 3 weeks of October) to travel in Japan and see a lot with few crowds in sight. But do note that October travel is also popular with Japanese domestic tourists, and this plays out primarily on weekends in high-value getaway locations near large cities (i.e., near Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto).

In terms of weather, October in Japan is basically perfect. There are no typhoons, heavy rain, or frost in October. And daytime temperatures on Honshu near sea level are pleasant. Along the Tokyo to Kyoto Golden Route expect daytime temperatures of 15-17 °C (59-62 °F) dropping to around 9-11 °C (48-52 °F).

But please do note that the last 10 days or so of October can be either crowded or extremely crowded on weekends near big cities and daily in Kyoto and Nara, especially. Kyoto receives 50 million domestic Japanese tourists every year. And between mid-October and late November Kyoto welcomes up to 15 million Japanese tourists. For foreign tourists this means crowds in places they expected to be serene and peaceful and problems finding hotels and inns that have rooms available. While it can be an issue, planning ahead helps a lot and my unique itinerary designs can be used to deal with overcrowding in Kyoto and elsewhere.

In the Japanese tea ceremony, the month of October has been poetically captured with “goma” associations that capture the essence of each 10-day period: early October , mid-October , late October . These key words and themes that have been classically repeated in Japan for more than 1,200 years. The October goma key words can help you “imagine” what to expect when you travel in Japan in that month. Early October themes: Ochi ho fallen rice grains; Yamaga mountain village houses/cottages. Mid-October themes: Ogurayama, Arashiyama Kyoto mountains famous for their autumn foliage; Hatsu Momiji first red maple leaves of autumn. Late October themes: Shorai wind blowing through pine trees.

Other well-known October themes include wind, colored leaves, chestnuts, autumn grasses, wild mushrooms, kaki persimmons, and mountain paths.

October in Japan is very much alive with the harvest season, and this means rice, autumn fruits, and tasty vegetables. October’s cold water currents and colder water in general is also excellent for the seafood harvest.

And October is the most wabi month of the year in the Japanese tea ceremony and in traditional aesthetics in general. Wabi refers to simple, rustic beauty and October is very much the best month of the year for these “concepts.” This is especially true in traditional village settings and in the major old temple garden complexes all over the country.

To summarize, October Japan travel is outstanding for the first 3 weeks and then great but challenging for the last week (i.e., crowds in Kyoto, Nara and around Mount Fuji). The weather is great, and the autumn harvest delights are sure to please no matter where you eat.

- Japan October travel food highlights

- Japan October travel tree and flower highlights

- Japan October travel festival highlights

- October is the beginning of fall kaiseki haute cuisine

- A Conversation with Master Photographer Mizuno Katsuhiko

Content by Ian Martin Ropke, owner of Your Japan Private Tours (est. 1990). I have been planning, designing, and making custom Japan private tours on all five Japanese islands since the early 1990s. I work closely with Japan private tour clients and have worked for all kinds of families, companies, and individuals since 1990. Clients find me mostly via organic search, and I advertise my custom Japan private tours & travel services on www.japan-guide.com, which has the best all-Japan English content & maps in Japan! If you are going to Japan and you understand the advantages of private travel, consider my services for your next trip. And thank you for reading my content. I, Ian Martin Ropke (unique on Google Search), am also a serious nonfiction and fiction writer, a startup founder (NexussPlus.com), and a spiritual wood sculptor. Learn more!

Japan October travel food highlights

The autumn harvest wonders of October are especially connected to vegetables, fruits, expensive matsutake mushrooms, chestnuts, yuzu citrus fruit and pricey gingko nuts.

In the category of vegetables October is the time to enjoy the wonders of Japanese sweet potatoes and other potato varieties.

In October you will also find the fruit harvest in full swing and this means everything from grapes and pears to chestnuts, persimmons and apples.

Kaki persimmons: A typical and breathtaking October scene in countryside Japan: ripe orange kaki persimmons etched against a bright blue autumn sky. Kaki are for looking at and they are for eating. If fresh off the tree, they are called amagaki (sweet kaki). Dried persimmons or hoshigaki are made from a persimmon variety known as shibugaki. Hoshigaki at their best are dried in the sunshine of autumn and early winter beneath the eves of traditional farm houses all over Japan. Kaki persimmons are full of vitamin C and can be found in all big fruit stores, especially those in the basements of Japan’s top department stores.

Mushrooms everywhere: And most of October is also mushroom season and in Japan this means an abundance of choices, textures and tastes. Look for these mushrooms on your dinner menus in October: shiitake mushrooms, shimeji mushrooms, enoki mushrooms and maitake mushrooms. If you have money to spare then you want to order matsutake mushrooms and the famous soup made from them. The favored way to prepare matsutake is to lightly grill them and then eat them immediately. If you are simply interested in seeing them, there’s a well-known shop that specializes in them in downtown Kyoto, about thirty meters north of Sanjo on Teramachi. Or just go to any high-end department store gourmet basement and you see these prized mushrooms (gun battles have broken out in British Columbia to control matsutake territory!). Looking at them, by the way, is free of charge. Just don’t touch or you will have to buy them! Four or five matsutake usually sell for Yen 8,000-10,000.

Yudofu tofu cuisine: Kyoto is famous for its many yudofu restaurants, many of which are concentrated around huge Zen temples like Nanzen-ji. Yudofu consists of fine tofu (as the main ingredient) and a wide variety vegetables cooked in an earthenware pot filled with kelp soup-stock. The pot is set up on a burner in the center of the table. Yudofu is a body-warming kind of vegetarian cuisine which can be easily prepared at home.

Nabemono hotpot dining: Nabemono, a highly popular form of Japanese communal cuisine, is prepared on gas burners right at your table. It is also referred to as hotpot cuisine. Ingredients can include fresh vegetables, chicken, pork, beef or fish, and, on occasion, noodles. The main nabes styles are: 1) Sukiyaki: thinly sliced beef sauted in mildly sweetened soy sauce in a shallow iron pan with tofu, mushrooms, spring onions, etc., and then dipped, hot, into a bowl of beaten raw eggs. At the end of the meal udon noodles are often served to soak up the last of the sauce. 2) Shabu-shabu: sliced tender beef and vegetables cooked in a brass pot of clear broth. Cooked pieces are then dipped in either one of two sauces: a vinegar sauce, called ponzu, or a sweet sesame paste, called goma dare. 3) Mizudaki: This popular hot pot combination combines chicken chunks and vegetables boiled in broth, which are then dipped in a special sauce made of soy sauce, lime juice, and spices. 4) Botan nabe: This cuisine is unique: thinly sliced wild boar meat simmered together with vegetables in a light broth. 5) Chanko nabe: This style of nabemono is exceptionally popular among sumo wrestlers trying to “bulk up.” Chanko nabe can pretty much include anything: vegetables, yudofu, fish, shrimp, and chicken.

- Japan October travel food highlights

- Japan October travel tree and flower highlights

- Japan October travel festival highlights

- October is the beginning of fall kaiseki haute cuisine

- A Conversation with Master Photographer Mizuno Katsuhiko

Japan October travel tree and flower highlights

In addition to the changing colors of the leaves all over Japan, especially at higher elevations and way up north (Aomori and Hokkaido), October is also wonderful for flowers and bushes. And the ginko tree and its amazing golden foliage is spectacular in October and should be looked for where ever you travel!

Cosmos Flowers: Nicknamed akizakura (autumn cherry blossoms), cosmos are probably the first flower that the Japanese think of in autumn. Cosmos come in pink, orange and white and blow in the breeze like graceful dancers. Cosmos can be seen in nearly all countryside locations in October all over Japan (they come and fade earlier at higher altitudes and “up north”). In Tokyo’s Showa Kinen Park cosmos can be seen at their perfect best until early November.

Chrysanthemums: Though few tourists realize it, the kiku chrysanthemum are symbolic of Japan’s imperial family. They stay in bloom for a long time and the imperial family has been in “bloom” for a very long time. Chrysanthemums figure prominently in Japanese literature and art. And they decorate one side of 50-yen coins. Growing ornamental kiku flowers in a variety of shapes and styles is very popular in Japan, even today. And chrysanthemum festivals and competitions are held throughout the country in October and November as well as in huge displays at major temples and shrines. Note: Do not give someone kiku flowers as gift as they are strongly associated with Japanese funeral practices.

Higanbana Red Spider Lilies: Known as higanbana in Japanese, red spider lilies (cluster amaryllis) bloom around the time of the autumn equinox in late September to early October all across Japan. These vibrant red flowers have a somewhat darker side to them, however, as they are considered a sign of loss or death and grow abundantly in the wild near cemeteries.

Osmanthus: Known as sweet osmanthus or fragrant olive in English, kinmokusei is a vivid orange flowering tree native to. The slightly citrus-like fragrance is sure to make any nature walk near these trees a pleasant one for the nose.

Early Momiji maple viewing locations on Hokkaido: Daisetsuzan National Park: Hokkaido is the first place in Japan to experience majestic autumn colors every year. In October, stunning colors can still be enjoyed by hiking into the higher elevations around Mount Asahidake, Ginsendai or Kogen Onsen. Shiretoko National Park (until mid-October): The best spots to see the fall colors on the Shiretoko Peninsula are the Shiretoko Pass in early October and the Shiretoko Five Lakes area in mid-October. Noboribetsu (until mid-Oct.): The trees surrounding Noboribetsu's amazing hell valley and near the sulfurous ponds further up the forested slopes, create a stunning contrast in October. Onuma Park (most of Oct.): Located near the southern tip of Hokkaido, Onuma Park sees autumn colors in the second half of October. The colors can be enjoyed on pleasant easy walk along the park's ponds.

Early Momiji maple viewing locations in the Tohoku region (north of Tokyo by bullet train): Hachimantai (most of Oct.): Some of the most spectacular fall colors in Japan can be seen in the Hachimantai mountains in western Iwate Prefecture (about 4 hours north of Tokyo by shinkansen bullet train). Good locations include the top of Mount Hachimantai, Goshogake Onsen and nearby Onuma Pond, Tamagawa Onsen, and Nyuto Onsen. Lake Towada and Oirase Stream (late October): One of Japan's most famous autumn season spots is Lake Towadako and its Oirase Stream in Aomori Prefecture. It is possible to follow the stream through a colorful forest settings for several kilometers along a walking trail.

Early Momiji maple viewing locations in Japanese Alps: Tateyama Kurobe Alpen Route (all of Oct.): Because of its high altitude the Tateyama Kurobe Alpen Route offers exceptional autumn vistas from late Sept. to early Nov. The area is about 2 hours from Tokyo by shinkansen and about 4 from Kyoto.

- Japan October travel food highlights

- Japan October travel tree and flower highlights

- Japan October travel festival highlights

- October is the beginning of fall kaiseki haute cuisine

- A Conversation with Master Photographer Mizuno Katsuhiko

Japan October travel festival highlights

CEATEC Japan (early Oct.; Chiba, near Tokyo): Japan's largest consumer electronics show showcases new technologies every year in a huge space. Every year the robots get better and better. Tokyo Yosakoi Contest (early Oct.; Tokyo): Probably Japan’s biggest yosakoi dance contest, which happens all over the Ikebukuro area of Tokyo. Maiko & Geiko Autumn Practice Performances (10/1-18; Kyoto): The finals of the annual practice performances for the Kamishichiken entertainment district offer the visitor a great chance to see these famous dances set to special music. Kamishichiken Kotobuki-kai (10/9-13): 16:00; Tel: 461-0148. Gion Onshu-kai (10/1-6): 16:00; Tel: 561-1115. Pontocho Suimei-kai (10/15-18): 16:00; Tel: 221-2025. Nagasaki Kunchi (10/7-10/9; Nagasaki): This major festival, which dates to 1634, is influenced by both Chinese and European cultural themes. The festival plays out all over the city of Nagasaki and is well worth the trip. Takayama Autumn Festival (10/9-10/10; Takayama): This is the biggest annual festival in the mountain town of Takayama. The festival is focused on 11 tall floats, attractively lit with chochin lanterns at night. The floats all have unique mechanical marionettes that have been “programmed” for performance events. Mibu Kyogen (10/11-13; Kyoto): Mibu-dera Temple’s Dai Nembutsu Kyogen or Mibu Kyogen features comic skits mimed and danced to the accompaniment of drums, gong and flute, and have been acted out for hundreds of years. Don’t miss them! Near the stage, people sell food and souvenirs. Performances are held continuously between 13:00 and 17:30; Tel: 841-3381. Niihama Taiko Festival (10/16-10/18; Niihama, near Matsuyama): This Shikoku island festival (near Osaka) features 47 huge and heavy floats shaped like giant taiko drums. Teams of about 150 men bounce the floats wildly in the air to show their team spirit. Sometimes, the float teams try to knock over opposing teams by ramming them. Nijugo Bosatsu Oneri Kuyo (10/19; Kyoto): In this unique ceremony at Sennyu-ji Sokujo-in Temple , children wear gorgeous brocade costumes and masks, representing various Bodhisattvas, divine beings who have chosen to live on earth to help human find the path to salvation. At 13:00 in a secluded valley, one km east of Tofuku-ji Stn. (Keihan and JR lines); Tel: 561-3443. Hatsuka Ebisu Festival (10/19-21; Kyoto): Ebisu is one of the Shichifukujin, the Seven Gods of Fortune, those irreverent and materialistic folk deities who are often depicted aboard their gorgeous treasure ship. Ebisu, the cheerful, bearded god takes care of business, travel, and fishing. The Hatsuka Ebisu Festival dates back to the Edo Era (1603 - 1868) when Kyoto's merchants, returning from business trips to Tokyo, would visit this shrine to give thanks for a successful and safe journey. During the festival, the shrine sells lucky branches of bamboo (decorated with treasure boats, coins, straw rice bales, and other amulets). People carry these back and hang them in their shops or homes. Many small stalls will be selling their wares, so the atmosphere will be as jovial as Ebisu himself. You'll be sure to have fun whatever your economic condition. The shrine is located on Yamato-oji south of Shijo; Tel: 525-0005. Jidai Matsuri (10/22; Kyoto): The Jidai Matsuri is one of the biggest traditional festivals in all of Japan. The main attraction is the long parade of people dressed in 9th-century clothing, who walk slowly from the Old Imperial Palace to Heian Shrine. Kurama Fire Festival (10/22; Kyoto): This festival is super popular with the Japanese and for good reason. The village of Kurama becomes an open-air museum on this day (starting from about 16:00) including samurai displays, men and boys in authentic historical clothing, and a wild night of giant flaming torches and sake consumption. Tip: get there early and leave early.

October is the beginning of fall kaiseki haute cuisine

The distinctive kaiseki cuisine style developed from the age-old traditions Kyoto in parallel with the rise of the Japanese tea ceremony from the late 16th century onward. The essential flavors that characterize this Japanese haute cuisine are subtle, and draw on the ever-changing tastes, shapes and colors of the surrounding area's seasonal ingredients.

Kaiseki meals are served in courses, aesthetically arranged in small portions, on exquisite Kyoto ceramics and lacquerware. Kyoto kaiseki cuisine is lightly seasoned, allowing the natural flavors of the ingredients used to stand out.

There are two other styles of kaiseki: 1) a less formal style served at parties, where. appetizers are followed by several courses arranged on a lacquered tray with sake; a bowl of rice and pickles are served at the end of the meal. 2) chaseki, which is served at long tea ceremonies.

Kaiseki or Kyoto Cuisine: Food as fine art

Kaiseki evolved from the very formal, almost ritualistic, eating patterns of the imperial court. In the Muromachi period (1333-1576) a new type of food favored by the warrior class evolved into cha-kaiseki as part of the overall aesthetic of the tea ceremony.

The term cha means "tea", while kaiseki means "breast stone". Zen monks ate only two meager meals a day and some would place warmed stones inside their kimono to calm their hunger pangs. As the ruling classes adopted the tea ceremony, the stone became the light meal before drinking the bitter, dark green tea. The master kaiseki chef is the product of a very wide, long and rigorous period of training that includes cooking skill, art appreciation, and a fairly sophisticated knowledge of Japanese cultural history. The master chef kaiseki chef creates works of art with seasonal ingredients (and even exotic things from abroad) that both please the eye and the tongue. Experience the world of beauty and food: enter the world of kaiseki (also known as Kyoto cuisine). Some eating tips: 1) If you drink, sake goes best with kaiseki. If you don't, then choose either green tea or the less exotic-tasting hoji-cha. 2) When something is served hot, you eat it as soon as possible. For an excellent selection of kaiseki restaurants, see Kyoto Cuisine on pg 9. Many places serve a very inexpensive mini-kaiseki course, so don’t worry about your budget too much!

Kyoto kaiseki, or haute cuisine, is among the Old Capital’s more rarefied and expensive treats. Fortunately, there are also inexpensive “mini-kaiseki” versions that won’t unduly stress your wallet, and if at all possible, this is something that should be experienced at least once. For kaiseki is not just about food; it encompasses nearly all mood-enhancing aspects of traditional Japanese living, characterized by seasonal ingredients, colors and motifs.

Modern-day kaiseki developed from the virtually ritualistic cuisine of the Japanese imperial court, which had created its own highly stylized version of food based on the traditions of the Chinese Tang dynasty. By the Muromachi period (1333-1576), with the unquestionable rise in the stature of the samurai class, kaiseki was being served on lacquered, high-footed trays set in front of each guest on the tatami mats.

Today, kaiseki preparation is regarded as a sophisticated culinary art that requires many, many years of training, and considerable cultural knowledge. Kyoto is home to many of Japan’s finest kaiseki establishments. Prices usually start around ¥10,000 for dinner, with lunch at about half that. And remember, kaiseki cuisine goes best with sake, green tea or hoji-cha tea, but there are more than a few avant-garde kaiseki establishments that also understand wine.

- Japan October travel food highlights

- Japan October travel tree and flower highlights

- Japan October travel festival highlights

- October is the beginning of fall kaiseki haute cuisine

- A Conversation with Master Photographer Mizuno Katsuhiko

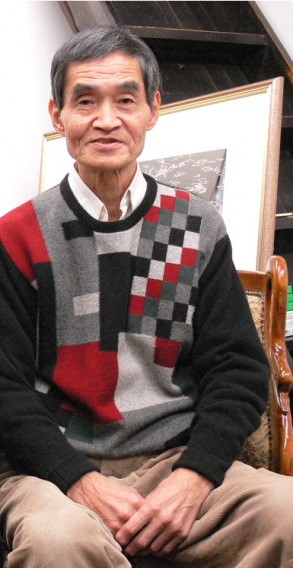

A Conversation with Master Photographer Mizuno Katsuhiko

Mizuno Katsuhiko is probably Kyoto’s best-known photographer, and his name is well-known all over Japan. He grew up in Kyoto’s Nishijin district, which is technically the eastern end of the Silk Road. Nishijin’s silk textile looms still click away today and some of the unique aspects of social life in this district also remain. There are less kids running around but the adults you meet on the streets are truly part of something, a community, that few others in Japan can claim as deeply.

Mizuno Katsuhiko’s photography books span the world of traditional Japan from gardens and machiya (traditional townhouses) to temples and shrines. You can find a few of his bestselling titles on Amazon (before you come to Japan) and in good bookstores all over Kyoto and Tokyo. Look for them and you will find them!

YJPT: How is it that you became a photographer? Was it your childhood dream?

Mizuno: I was born in the Nishijin textile district, which is Japan’s most famous and oldest area for weaving arts. My grandfather was a textile designer in the early Meiji period (1868-1912), when the Nishijin area was still very vital and prosperous. I was very fortunate to grow up in Nishijin, home to so many craftsmen and an intense blend traditional culture and art. I guess the first job I dreamed of as a child was to be some kind of artist. To create something beautiful for other people seemed to be the highest goal I could think of. When I was about 10 years old, and still in elementary school, my father gave me my first camera, and my creative dream began in earnest. I spent hours and hours taking pictures and never got tired of learning everything there was to learn about photography. With old post-war Kyoto as my backyard, you could say I was in picture-taking paradise. Needless to say, my interest in taking pictures continued throughout my years as a student in junior high school, high school and university.

When I graduated from university, I decided to become a photo journalist, and so I joined a newspaper. It was not really a practical decision. I just thought that what could be better than the newspaper paying me to take great photos of Kyoto. Unfortunately, as a staff cameraman, I found that I had much fewer opportunities to take photos than I expected. I was in the office a lot. And, even worse, many of the assignments were dry and uninspiring. As a student I could do what I wanted, when I wanted. I was always doing something creative and without limits. In the newspaper world, I soon discovered that all my dreams were quickly turning to nothing more than boredom, frustration, and sadness. So, I did the only thing I could do. I quit. That was well over 30 years ago.

YJPT: So, what did you do then?

Mizuno: After leaving the newspaper, I started taking photos of Kyoto scenery and selling them to magazines. It was the perfect time to go solo, because there were so many new magazines to sell to in the late 1960s. Japan was booming. Even though I was quickly becoming successful as a free-lance magazine photo journalist, I still wasn’t satisfied. What I ultimately wanted to do was publish my own books of photographs. To reach the self-publishing level, I had a lot to learn. To get there, I studied all aspects of book planning, editing, printing, everything.

That was a long time ago. Since that time, I have published 95 books of photos and essays, of which 90 are on Kyoto. Sometimes, I write the text myself, but mostly I spend my time on just the photos. Generally, from start to finish, the entire process for one book takes about two and half years. For the photos alone, I need about 18 months.

My book on Honen-in Temple came out over 20 years ago. Only 6,000 copies were published, and it’s now out of print, but it was very influential for me as many temples have commissioned me to create books for them on the basis of this book’s reputation. These kinds of books are usually used as a kind of public relations tool for temples to show off their special seasonal aspects and cultural treasures. They take a long time, because the temple’s demand the best and they are willing to pay for the best.

YJPT: A lot of your work is devoted to Japanese gardens and buildings. What are your feelings about Western gardens and architecture?

Mizuno: I don’t know a lot about Western gardens, but from the little I know I find the Japanese garden to be much more passionate. European and even Chinese landscape design seems to be driven by a strong rational element. Western buildings and gardens are almost always perfectly symmetrical. On the other hand, the left and right side of houses in Japan are usually different, even if only subtly. And Japanese gardens have a so-called symmetry that is totally different from Western designs. The Japanese like things to be vague and abstract.

Western gardens are geometrical exercises. Japanese gardens inform us of the changing seasons, and they change with time. A traditional Japanese garden now and in 100 years is quite different. Japanese people, until only quite recently, found old things to be inherently relaxing. The older I become the more I am instinctively drawn to old things. I have owned six houses in my lifetime: three new ones and three old ones. I live in an old one now and I will never want anything else.

YJPT: Most of your photos are of gardens and buildings. Do you also photograph people?

Mizuno: I have always wanted to photograph people. But I find that Japanese people always demand to be taken at their very best. They want to appear beautiful in a classical way in the photo. This makes it difficult for the artist. Japanese people are not good at expressing themselves. They are too self-conscious. They think too much about the camera.

YJPT: What do you remember about your childhood?

Mizuno: I remember that the days were long. The pace of life was relaxed and natural. And the responsibility of the community was shared in a special way. We would keep the pine forests around our neighborhood free of brush and dead trees. By keeping pine forests clean, we were sure to gather a rich harvest of matsutake mushrooms, a delicacy. Now most of our matsutake come from Korea, China and Canada.

Another thing that I remember about the old days was that children played outside on the street. Even if it was raining, the kids would huddle under the wide eaves of our machiya townhouses and play. And then after the rain, they would have a ball playing in the tiny ponds in the streets. You could also see many kids hanging around the local dagashiya sweet shop. They had lots of fun and lived the seasons the way children are supposed to: naturally and with lots of play time. I don’t see such children any more. Today it’s seems to be all about study and study and study. It’s sad, but that’s the way the world is.

YJPT: What are your feelings about the way Kyoto has changed?

Mizuno: Kyoto is the only large Japanese city that was not destroyed in World War II. Most of Kyoto’s old townhouses were still standing a few years ago. But now they are being torn down in record numbers. Houses made of wood, earth and paper suit the Japanese climate and the Japanese way of life. I do not really understand why people want to live in new buildings. It has such a negative impact on the way people interact. Kyoto has always been special, because Eastern and Western design co-existed harmoniously here. This was unique to Kyoto. Now, Kyoto is quickly becoming the same as other Japanese cities. This has necessarily changed the quality of life and the way people relate to each other.

In the old days, relations between Japanese people were much looser. It was common to be asked “Where are you going?” if one was walking through the neighborhood in one’s best clothes. People from Tokyo found this question made them feel uncomfortable because they didn’t want to tell people where they were going. But the question wasn’t meant to be taken in that way. All people wanted to hear was that you were going into town. And then they would always add, “Have a safe journey and return in good health”. In the old days life was more intimate. We freely entered the homes of others in our neighborhood. There were hardly any locked doors and no rules about personal space. In a sense, the neighborhood was like one big happy family. I’m lucky to still have a little of all these things in my neighborhood. Nishijin isn’t like it was when I was a kid, but it’s close. I feel privileged to still live in a place where the old ways go on, as they go on inside my soul, and in my life as a chronicler of the old world continuing to grow and age in the new.

Japan month by month private travel & culture summary index

Japan spring travel: Mar, April, May. Learn more!

Japan summer travel: June, July, August. Learn more!

Japan autumn travel: Sept, Oct, Nov. Learn more!

Japan winter travel: Dec, Jan, Feb. Learn more!

Content by Ian Martin Ropke, owner of Your Japan Private Tours (est. 1990). I have been planning, designing, and making custom Japan private tours on all five Japanese islands since the early 1990s. I work closely with Japan private tour clients and have worked for all kinds of families, companies, and individuals since 1990. Clients find me mostly via organic search, and I advertise my custom Japan private tours & travel services on www.japan-guide.com, which has the best all-Japan English content & maps in Japan! If you are going to Japan and you understand the advantages of private travel, consider my services for your next trip. And thank you for reading my content. I, Ian Martin Ropke (unique on Google Search), am also a serious nonfiction and fiction writer, a startup founder (NexussPlus.com), and a spiritual wood sculptor. Learn more!